Marketers are told to focus on winning new buyers to build long term growth…but math proves this rarely works.

There are two truths about growth: 1) the only way to sustain a share increase is by increasing buyer retention rates, and 2) brand penetration rate differences across brands collapse over extended time horizons as buyers switch among many brands during their consumer lives. So, basically you get trial for free if you wait long enough but sustained growth requires greater retention which you have to work hard for.

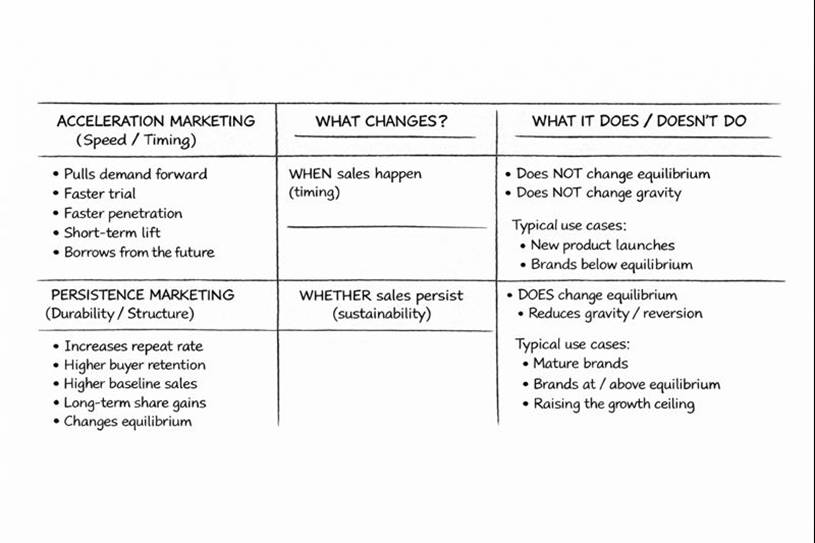

I propose that these two effects… acceleration vs. persistence…are distinct and while they each serve a purpose, should be thought of as two forms of marketing.

When you target non buyers for conversion, that is acceleration. When you target existing customers, favorables or movable middles, that is persistence marketing that raises your retention rates leading to sustained growth.

Marketers: are you spending too much time and resources on acceleration and not enough on persistence? On MMA “brand as performance” studies we found this to be true.

Laws of growth: a frozen pizza example

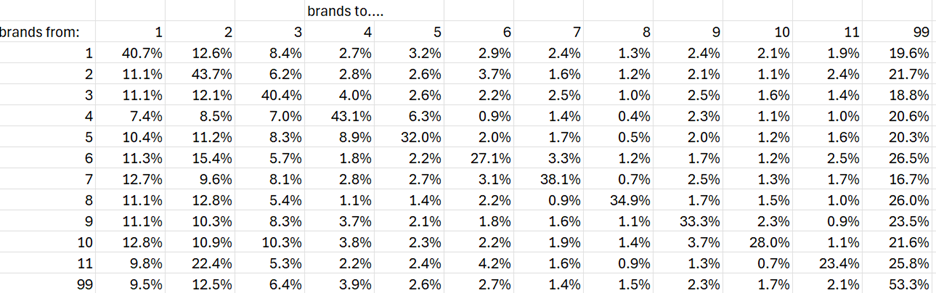

See the included Markov brand-switching matrix (source: Numerator) for the frozen pizza category (bottom of blog). It covers 11 major brands plus an “all other” bucket (which includes private label).

Each row shows what brands people buy on the next purchase occasion of frozen pizza, conditional on what they bought last time…the rate of repeat buying (diagonal terms) or switching to any other brand (the off-diagonals).

Two patterns tell us a lot about the laws of growth

There is a positive probability of buyers moving from any brand to any other brand (no zeros in the matrix)

When this is the case, linear algebra tells us that every brand will generate substantial long term penetration organically…more than enough to hit any growth target.

Yes, marketing can make the trial process happen somewhat faster; that’s why I call penetration-focused strategies acceleration marketing.

Retention rates vis a vis market share

Look at the diagonal of the matrix. National brand repeat rates range from 23% to 44% while market shares range from 2% to 16%. That tells us brand loyalty is real. Going further, the shares for each brand are strongly correlated to their repeat rates. (Math explains why this has to be.)

The bottom line is that retention, not trial, is what determines where brand shares ultimately level off.

The analytic power of the Markov matrix

Once you have a brand-switching Markov matrix, you can do some very powerful things.

- Determine equilibrium market shares

There exists a share distribution such that if you apply the switching probabilities to it, you get the same distribution back. That is the set of equilibrium shares implied by the conditional probability structure of the market. This is actually straightforward to solve for.

Remarkably, this equilibrium is independent of today’s shares. Hence, a boost in sales due to advertising or promotion will be temporary UNLESS you increase buyer retention.

- Growth: calculate what it would take to support a given higher share

In our frozen pizza data, suppose Brand 3 wants to grow its market share by 2 points and sustain it.

Using a particular analytic method, you can solve for how each and every entry in the switching matrix would need to change to support that new equilibrium.

When I did this, there was only one solution and it was unambiguous:

Brand 3 would need to increase its buyer retention rate by about 1.6 points PLUS every other brand’s repeat rate would need to fall slightly to “fund” this increase.

This is not a modeling assumption. It is dictated by the conditional probabilities of the matrix and the laws of linear algebra.

Now, let me share what really blew my math mind…I calculated the needed increase in repeat rate from a Dirichlet distribution and I got THE SAME ANSWER.

This suggests I have discovered a fundamental truth via convergence from two very different math approaches.

When to use either marketing approach

To be clear: acceleration marketing is not always “bad”, but it is limited to specific use cases.

Here’s a comparison table.

Callouts: Acceleration marketing IS especially important for new products. Retailers get impatient. Investors get impatient. But for mature brands, if you want growth that sticks, persistence marketing is needed.

“But don’t we still need new customers?”

Yes. And here’s the final piece of the puzzle. When you increase buyer retention, penetration rises automatically over time. Remember the brand growth scenario up above: to sustain growth, brand 3 needed a higher repeat rate AND all the other brands’ repeat rates had to decline. That means somewhat higher probability of switching into brand 3.

Final takeaways

For marketers:

Accelerating brand penetration isn’t sustainable growth — it’s timing. And the acceleration costs a lot because non-buyers are much less responsive to advertising.

Rethink your balance of acceleration vs. persistence and which tactics are best for each purpose.

For analysts:

If you are not yet working with Markov brand-switching matrices, you are missing one of the most powerful tools available for diagnosing growth, decline, and market share sustainability. You can get a Markov matrix from many syndicated sources (e.g. shopper, credit card, or location data) or via the right questions in your survey.

Contribute to Discussion »